You Can Nurture Queer, Small-Town Network Effects With Food

Knock and open doors when you have something to spare

Quiet clicking noises were coming from our guest room. A soft young one we barely knew had been in there for hours, alone.

After finishing their shift at a local weed shop, a co-worker had dropped them at our place. We had agreed they could stay for a week, then we would all assess the situation together. After a slightly stiff but friendly initial chat, they had asked for our wifi password and excused themselves to their room. Now, they were quietly self-soothing with their games and socials.

Earlier that day we had learned, through a community group, that something had gone wrong for this kid at home. They said they were no longer welcome in their mother’s house (“you are 18 years old, so get out”), and put out a plea for a place to stay. We did not pry. My husband and I’s own home situations had been fraught, at points, when we were young. Being LGBTQI is like that. Unlike racial minority kids—whose parents at some point typically sit them down for “the talk” about racism—we queers1 grow up alone in our childhood home, with a lot of questions and little, if any, support. Sometimes, overt hostility and violence.

So, now we have a guest room. We welcome guests. All kinds.

We invited our young guest to help themselves to anything in the refrigerator. They did, so we kept cooking and packing away servings of leftovers-to-go throughout the week, though they turned down all offers to sit with us for a meal. The next week they told us they had made arrangements to move in with a co-worker, and sincerely thanked us for providing them a landing pad. It was a friendly encounter all around, and we still keep in occasional touch.

There is always some kind of click. Some button or pad emits a sound, and takes me to the next sentence, image, or video on the screen that eats a piece of my life every day. I sit here, tapping, taking in cultural markers created by groups of people with whom I have chosen some connection. Or, rather, in more cases, unchosen, invisible groups to which I have been assigned by my prior clicks.2

A lot of these words and images ask something of me. Typically, they ask for my outrage or heartbreak, followed by my money. Less commonly, some words and maybe a picture will appear from a real person, directly asking for specific help.

One of the benefits of the internet is that people can ask for help without feeling a flush of vulnerability involuntarily spread across their cheeks. A feeling they might feel if they had to ask for what they really need, face to face. Screens puts layers between us, making many things harder, but some things easier.

Like asking and learning when a neighbor really needs some help.

Network Effect: a positive feedback cycle by which participants gain more value as more and more other people choose to participate.

We always know when someone is at our front door, because the dog goes off more reliably than the door bell. All our friends know they will get a minute of barking before Izzy starts begging for scruffles and belly rubs.

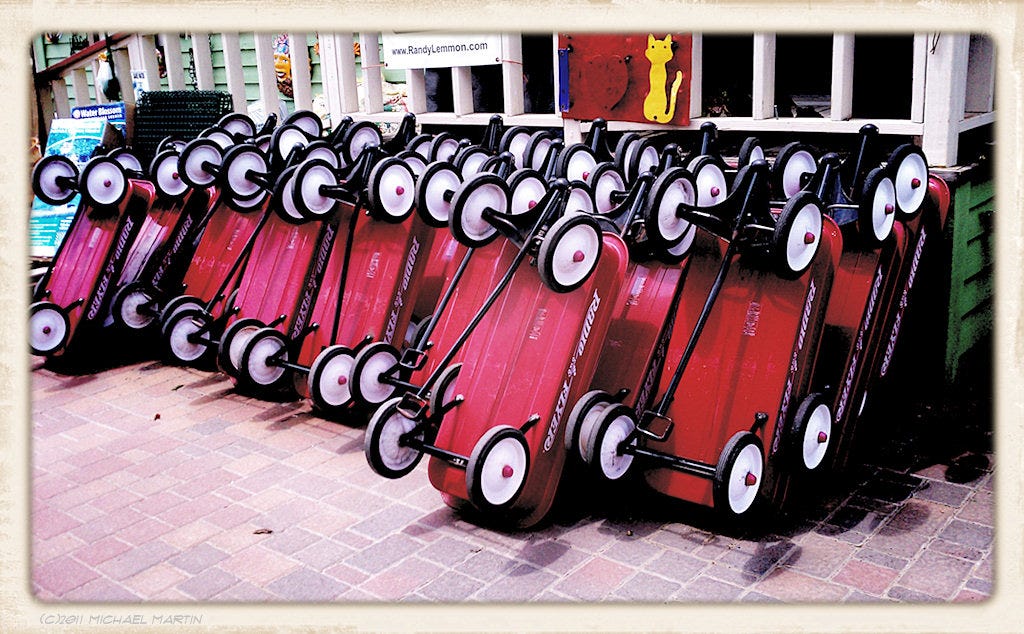

One afternoon, a few weeks back, I opened the door to discover three colorful young women, two at the door, and one at the sidewalk pulling a bright red toy wagon behind her. Twenty-somethings, sporting a variety of hair dyes, tattoos, and facial piercings. They cheefully identified themselves as “Helena Lesbians, collecting food donations for Helena Food Share.”

I’ll admit I paused, for just a second, to process this. Lesbians … knocking on front doors … in Helena, Montana, a town of 36,000 … as lesbians … to do such a basic and vital community task as helping out our local food bank. Out and proud door-to-door knocking was not something I could have even considered, back in the 1980s, when I was their age. Just imagining that is mind-bending. I was terrified to come out to my family, much less knock every door on the block.

So, I beamed at these three young women like some happy Dumbledore, and yelled excitedly to Michael. I ran to the kitchen, grabbed a shopping bag, and shoved in everything I could find in the cupboard. Pasta, canned tomatoes, beans, soup, all the standards, plus an an odd condiment or two, because gay.

Handing a fat bag of boxes and cans over to this trio made something click inside. Hard as it can be, the world changes in good ways, too.

I do not love the word “Queer.” It was bashed into my face in grade school, leaving a lasting impression. More problematically, the effort to reclaim it as a global descriptor, for the entire LGBTQ2SIAA collection of minority sexual orientations and gender identities, erases the vast diversity and divergent histories within this loose yet fairly effective political alliance. An alliance which has never been a singular, cohesive community, no matter how many non-profit rainbow warriors or corporate marketing departments may like to claim otherwise.

That said, I recognize the convenience of the term, along with its unstoppable use when there is no time or patience to explain everything it hides.

Like everyone, I am algorithmically segmented by my demographics, mostly without my knowledge or consent, so I can be profitably targeted with invasively customized ads. Yes, you are being surveilled, too. Yes, you can opt out.

https://redact.dev/blog/data-brokers-101-what-they-are-and-how-to-protect-your-info