Late Fees Made Me Build a Library of My Own

Bibliophilia in pursuit of personal authenticity

Parmly Billings was the son of Frederick Billings, the railroad executive for whom my hometown was named. His father never once stepped foot in town, but Parmly did, and died of renal failure there in 1888. He was 25 years old.

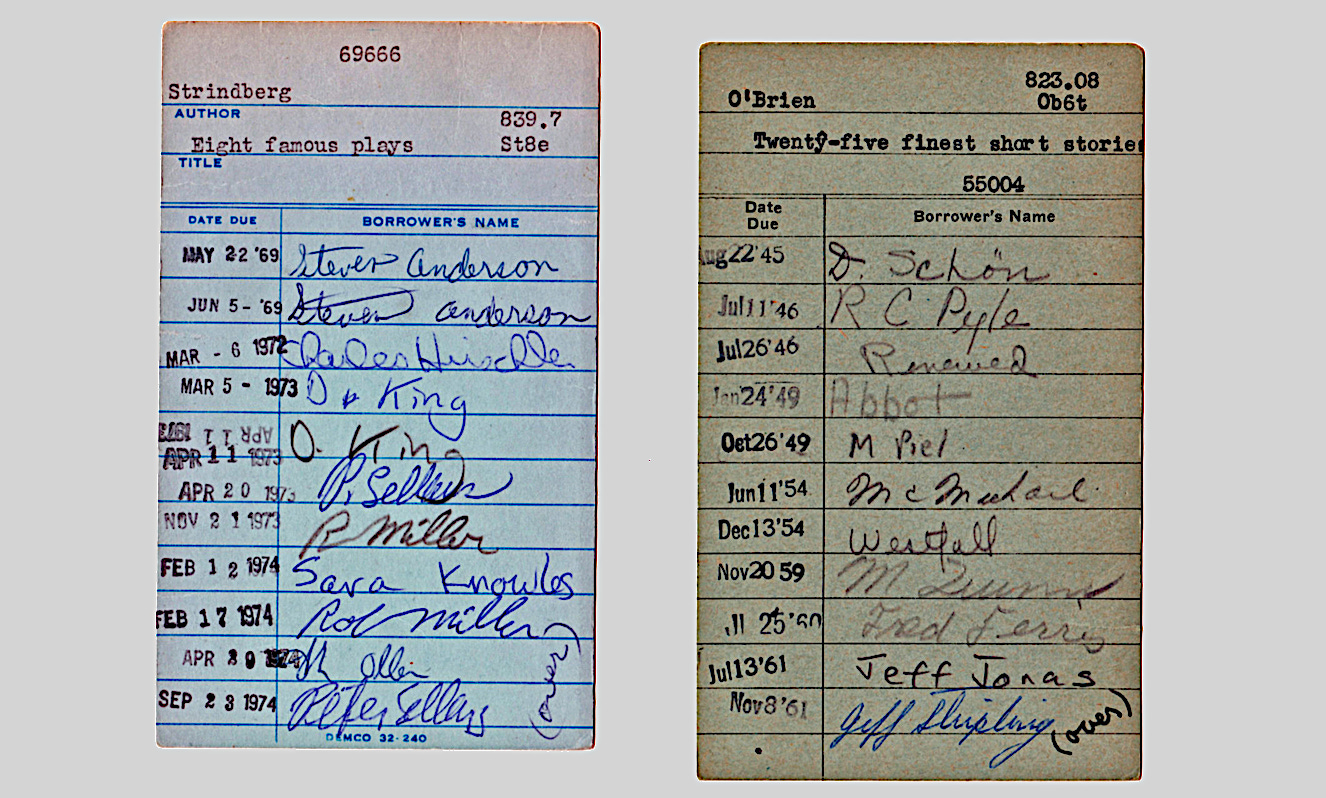

A beige metal machine sitting atop the curved white checkout counter of the Parmly Billings Library, circa 1974, was my nemesis. With each tap of a long silver bar, it took incriminating photos of book checkout slips. These photos held me accountable to return dates I readily forgot. The book were my friends.

The librarians wanted my friends back. After some hard lessons with late fees—and their big impact on my small allowance—I learned my bookish desires were better fed by diverting my funds into building a library of my own.

I’ve never stopped.

Those who know me, and our home, know my bibliomania is acute. I own thousands of books, five or so, though I have never counted. It is not a competition. It is a semi-regulated addiction.

When I was a kid, the public library was a safe haven where my mother could drop me off, then find me later, after her shopping, cigarettes, fabric hunting, visiting, bridge clubbing, and who knows what else, were done. Bookshelves babysat her eight year old.

If that sounds like bad parenting, then you are dating yourself into a later and much more sheltered generation. Yes, I also drank from the garden hose and rode my bike anywhere I liked. #feral #genx #resilience

I was a quiet child, polite to the librarians who grew to ignore me like one of the rubber plants scattered about the place. Which was fine by me. I knew they neither wanted my attention, nor would provide their own, unless I had a specific question. Nine out of ten of which got me directed back to the card catalog, to find another book for myself. Ten thousand more interesting thoughts surrounded me on the shelves than they could ever provide. I learned the Dewey decimal system long before my classmates.

I had only one major flaw as a young, avid, and regular public library user. When I checked books out, I would neglect to bring them back. For months.

Why would I send my friends away? Piles of books illustrated how boredom was impossible. Just open a different book. The copy of Where the Wild Things Are I first read in the library’s Children’s Reading Room was no doubt a first edition. I am sure I read it at least a dozen times, alongside dozens of others, seated at the low, round, blue seat-padded table, waiting for mom, in no hurry for her to arrive.

The library was my perfect world. Hell would break loose back at home, though, when the late fee bills arrived. I soon became used to “the look” I would get when I went to check more books out. They knew me. It was my walk of shame.

So, around the age of nine I quit using the public library so much, and began building a library of my own. Life was easier this way.

The personal relationship I feel between myself and a favorite book has never left me. It is not necessarily about the story. I am a connoiseur of the well worn mid-fifties trade paperback. Cover art was better back then; more confident and less overweeningly ambitious than today’s repetitive graphic explosions.

Used book stores are my nightclubs. I fall easily for soft corner curves that talk to me of lovers who have held this book before. Just please don’t write inside.

It would be silly to think I would read all the books I buy. That is not the point of a library. A library is a gatherum of possibilities that will remain when the lights go out, and greet us still when they return. It is the potential behind this notion that feels sexy as I stroke my keys, typing these words into just another flavor of backlit social media. My aging eyes do not track text on screens anywhere near so well as when reading words on paper, under good light.

Yes, E-Ink is better than a backlit screen, but it has no scent. It carries no love. You cannot hear a Kindle crinkle, or whisper as the pages flip. A flat box holding a screenful of words and pictures seems like a pimp presenting his wares. Want a bit of this? No? Something else? Welcome to the Internet. Have a look around.1

Just keep clicking. Even better, just scroll and keep scrolling, right?

It is hard to write about addiction. Last night, while shopping for Chex Mix supplies (‘tis the season), a young man, maybe 27, walked by us in the cereal aisle; eyes vacant, gait twitchy, cheeks shallow and scabbed. I did not see his teeth, but could guess. Meth does not treat bodies kindly. I wanted to be kind to him, somehow. I also know better than to offer anything directly to an addict, unasked. Their desires are clear, to them, and do not take well to interruption.

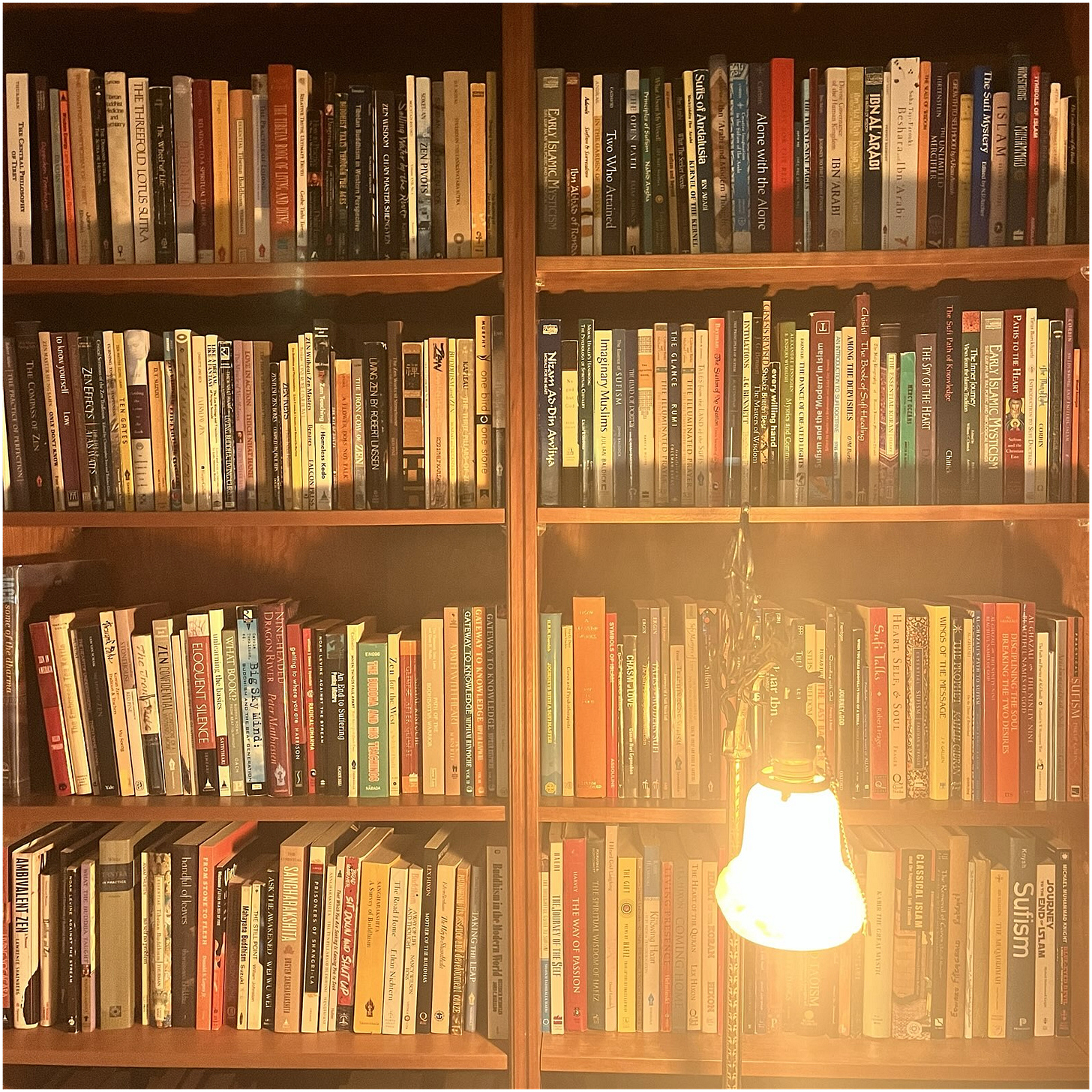

Do the five thousand books inside my home betray an addiction? If I am going to be honest, I have to say yes. Book buying gives me a dopamine hit. Pulling a favorite down, and paging through it, gives me a shoulder-drop full of relaxation, followed by a savory tinge of curiousity and recall. As my mother would say, “You can travel the world from an armchair.” My tastes are not narrow, but are fairly specific: religious studies (Buddhist, Sufi, Christian), philosophy, Masonry, modernist poetry, LGBTQ cultural studies, and literary nonfiction.

What are your own? Are you an addict? Is this problem manageable?

I rationalize pursuing my rushes by telling myself these books living on my shelves (and floors, and nightstands, and overstock in banker’s boxes in the basement) hold inherent cultural worth. They do so because they could still be read if the power goes out. They do so because only one percent of all books printed ever get a reprint. Which means each book I buy helps preserve thoughts and stories which could otherwise be lost. Which is a great and bloviating bit of bullshit I whip out for myself each time I find something, preferably used, that a shimmering inner compass tells me belongs on my shelves, in my collection.

A friend of mine owns one of, in my fairly well-experienced opinion, the world’s greatest bookstores. Through him, I know how naïve it is to think anyone will want my books after I die. If anything, I will need to leave money to someone so they will take them away, and maybe even care for them. My bookstore-owning friend tries to avoid sending books off to be pulped. Yet, there is only so much room in the shipping containers he keeps out back of his shop.

At some point, there is always curation. Shelves are finite, so we must develop our taste.

I will still buy books, though. And, I will hope they mean something more than money to someone ahead, just as they have to me. All my shelves full of ink and paper echo visions of reality I have had, on this particular trip around the sun, even if for only a moment. They will go away someday, just like me. Nothing is forever. But, until then, if the power goes out, you will know where to find me.

I can alway use this laptop as a serving plate.

"Welcome to the Internet,” Bo Burnham. If you have never, you should fix that.

Eighty miles west of Leo and three decades sooner, I rode my bike to the Carnegie Library of Big Timber. Two little old ladies worked there and stamped my books and my card.

In the seventies, my motorcycle took me back to Big Timber. I went in the library. The inside stairs creaked the same. I walked the short aisles and returned to the desk. "The only things different are the plastic laminate on this counter and the fluorescent lights," I reported to the librarian in charge. Then I told her where the Landmark books were, the Zane Grays and Hardy Boys. "And over there, a full shelf of the best: the Tom Swift books by Victor Appleton."

She leaned toward me and whispered, "The Tom Swift books are for sale downstairs." I would have bought them all, but, well, motorcycle. So I gave a quarter for "Tom Swift and his Airship." Still have it.

Thank you Leo.

Love this story. And one of my earliest memories is of sitting in the big room off the children’s section at Parmly for story time.